Dean's Update

May 3, 2024 - Aron Sousa, MD

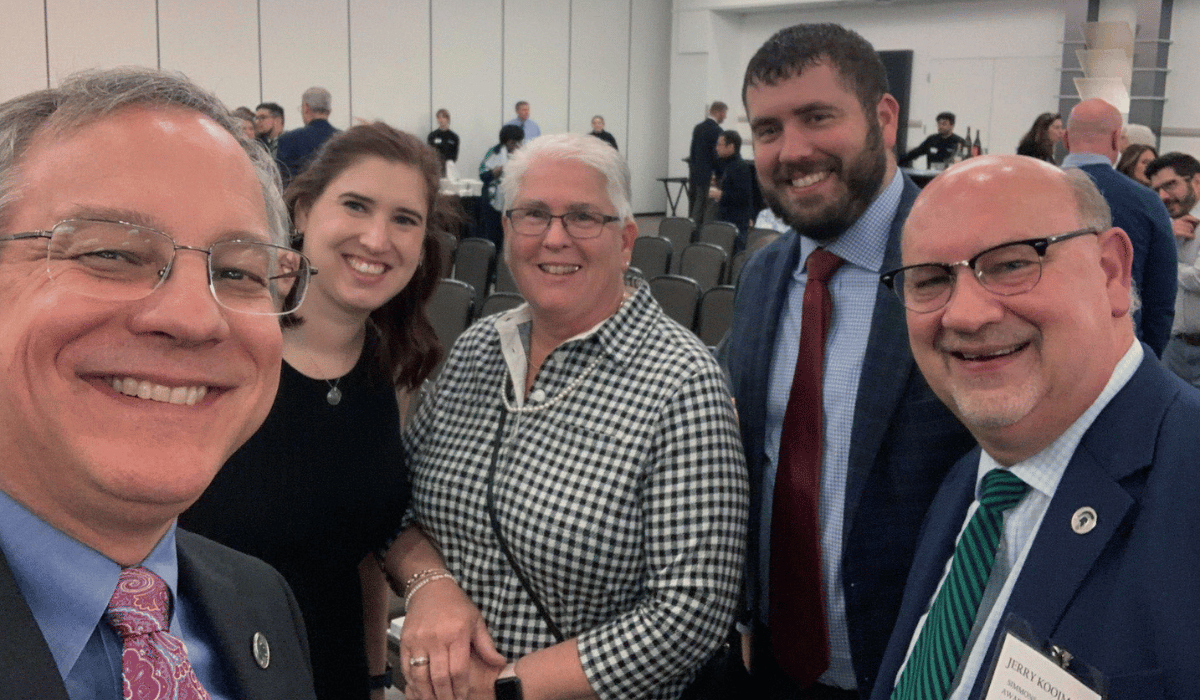

Aron and Jerry’s family celebrate Jerry! From the left after Aron, Katie Gonzales (daughter), Maribeth Kooiman (wife), Matt Kooiman (son), and Jerry Kooiman.

Friends,

This is a week of celebrations. Above is a picture from the All-University Awards reception during which Jerry Kooiman was awarded the Simmons Chivukula Award for Academic Leadership and all of the rights and privileges therewith. Tonight is the college’s Minority Banquet. Saturday is the MD graduation, when we celebrate our faculty award winners and new Spartan MDs. May the fourth be with us.

I am delighted to announce two additional members of our Advancement team: Laura Postma, associate director of development, and Nashay Cadle, development assistant.

Laura joins MSU after five years at Stanford Medicine with her most recent role as a development officer. Before her time at Stanford, Laura was a senior admissions counselor at Calvin University. She brings a blend of skills and experience, and a demonstrated track record of success in securing major gifts that set her apart from other candidates. Her experience in prospect identification and discovery, as well as grateful patient and cancer research fundraising, will certainly be an asset to our major gift work.

Nashay joins us from the college’s Office of Student Academic Services (OSAS); she is already a step ahead in her onboarding. She will be focused on supporting our development team, which is small but mighty. To be honest, our development team is much smaller than that of our peers, but we are very efficient. We spend pennies for each dollar they raise. The first day for both Laura and Nashay will be Monday, May 6.

April marked ten years since the changes in Flint’s drinking water that led to the Flint Water Crisis. There is a range of media tracking the anniversary of this tragic government created disaster, and you don’t need me to rehash the history. Like the pandemic, the water crisis laid bare failures in governmental action, as well as the racial and societal disparities in our communities. There are, however, a few lessons and carols I want to bring to the fore:

- Democracy saves lives. The functional decision-making office behind the water crisis was the emergency manager placed over Flint by the governor. This manager did not report to anyone controlled by the Flint electorate, and when the elected Flint city council tried to change the source of Flint’s water to address the issues, they were powerless to do so. The water looked and tasted dreadful, and the water was so tough GM switched its water source because the Flint city water was corroding auto parts! Any rational local elected official would have moved to fix it – that’s why democracy is a useful system of government. A democratically elected government has a feedback loop with the electorate that helps protect the health of a community.

Without the feedback loop, the emergency manager (and the state) could just say no to the people of Flint. The horrible water continued, which led to the corrosion of lead pipes and then to lead in people. The corrosive actions of the water on the pipes of the water system also likely depleted chlorine in the water making bacterial growth more likely. Significant portions of the 86 Legionella pneumonia cases and 12 deaths were probably related to the water crisis. I believe democracy would have changed this crisis and saved lives.

There was a meaningful and important racial component to the implementation of the emergency manager law, which particularly highlights why local electoral control is an important backstop to state and federal ignorance and incompetence. - We need community scientists. The unsung heroes of the Flint water crisis are the people of Flint who worked as community scientists. There was a core group of Flint residents, like LeeAnne Walters, who made key observations and sampled water in collaboration with the Virginia Tech team, which did a great deal of analysis showing the problems with Flint’s water. A part of our work as educators is to prepare the residents of our country to be good observers and thoughtful about the process of science. We need to prepare people to engage when scientific questions are key to our health and safety. Our job is not just to teach future scientists science, we need everyone ready to be a community scientist.

- Universities are the scientific safety net. The Flint Water Crisis was caused by a range of governmental mismanagement. It persisted, in part, because the state and federal system of scientific surveillance failed to capture the contamination of water and the uptick of lead in kids. Governmental agencies saw the spike in Legionella, but it was not clear whether there was one, or, as it turned out, multiple sources. In short, the government missed key scientific observations.

The science that carried the day was done by universities, namely the water engineering team at Virginia Tech and the Flint-based public health scientists at Michigan State and Hurly Medical Center, led by Mona Hanna-Attisha and, including but not limited to, Jenny LaChance, Dick Sadler, and Allison Champney Schnepp, a pediatrics resident in the MSU affiliated program at Hurley Medical Center. Faculty and students at West Virginia provided a similar safety net for the VW pollution fiasco. And, we all know that our governmental resources were overwhelmed by COVID-19. Universities, their faculty, and their students are a key source of scientific expertise and investigation when governmental (and industrial) science is overwhelmed or absent without leave.

The people of the College of Human Medicine were uniquely placed to be the collaborators of the people of Flint during and after the water crisis. In truth, Michigan State is the only non-governmental institution with the necessary skills, facilities, and talents to assist communities across the whole state. That is a remarkable responsibility and opportunity for us all.

Serving the people with you,

Aron

Aron Sousa, MD, FACP

Dean, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine