Inside the Castle: Studying Social Motivation in Young Children with Autism

May 7, 2025

Barbara Thompson, PhD, has been conducting research on neurodevelopment since her postdoctoral fellowship. As an undergraduate and then graduate student, she had a strong desire to take well-established translational neuroscience tools and apply them into clinical populations.

Barbara Thompson, PhD, has been conducting research on neurodevelopment since her postdoctoral fellowship. As an undergraduate and then graduate student, she had a strong desire to take well-established translational neuroscience tools and apply them into clinical populations.

"The beauty of science is the more questions you ask, the more answers you get, the more questions that actually opens up the door to," Thompson said.

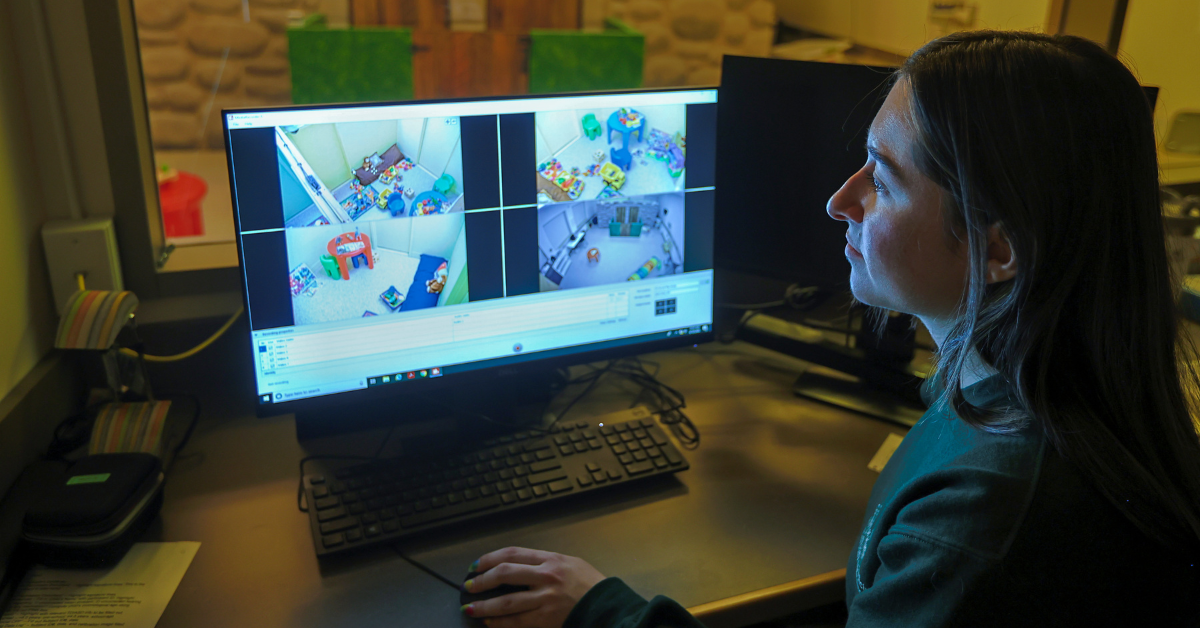

As a result, Thompson and her team were the first to demonstrate social conditioned place preference in humans. She’s using that technique to examine social motivation differences in kids with autism. The children, ages 2 1/2 to 5 1/2 years old, get to do what kids do best – play. Becca Ribbens brought her 3-year-old son, Leo, to the Social and Emotional Neurodevelopment (SEND) Lab inside the Secchia Center in Grand Rapids, where he plays inside a castle that’s just his size.

"I'm a nurse and I have history in the neonatal unit. To see different outcomes of children and their development, I think it's really important that research is done from a non-biased perspective with someone like Barbara who is able to take out some of the variables,” said Ribbens, a mother of three as she watched Leo play in the castle.

"This was very easy. It was fun. He enjoyed himself… I think if we can volunteer to help support research that can help other children in the future, why wouldn’t we do that?"

Ribbens learned about Thompson’s work at the Teddy Bear Health Fair, an MSU College of Human Medicine sponsored free community event aimed at promoting health awareness. Ribbens has a twin sister and took part in MSU’s Twin Registry (MSUTR) growing up. She understands the value of research and says she’s happy to give her time and her son’s time to the cause.

"As a nurse and as a young mom I see other children who have (autism). I thought it was something that my son and I could do," said Ribbens.

Leo doesn’t have autism but his participation in the study is important. Thompson and her team observe children who are neurotypical and those who have a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

Leo doesn’t have autism but his participation in the study is important. Thompson and her team observe children who are neurotypical and those who have a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

“When a kid is given a diagnosis of autism, that diagnosis means there are differences in social communication, but it doesn’t detail what those differences are, or how they come about,” said Thompson. “This task is designed to specifically tease out the individual differences in social motivation.”

The castle features two identical rooms with the same toys in each space. A social experimenter, often a College of Human Medicine student, interacts with the child in one of the rooms. When the social experimenter leaves, Thompson and her team measure the amount of time the child chooses to spend in each room.

"If they go back to that room where the social experimenter was, we can interpret that as a rewarding experience. It made the child feel good, they want to continue spending their time in that side of the castle,” said Thompson.

If disruptions in social interactions are driven by differences in reward and motivation, that’s mediated by different neuroanatomical circuits than those involved due to fear and anxiety.

“This research allows us to get an idea of what sort of neuroanatomical circuits might be involved for each young child experiencing differences in social motivation."

The research sessions end with the children watching a video on a laptop equipped with an infrared eye tracker.

The research sessions end with the children watching a video on a laptop equipped with an infrared eye tracker.

"We’re trying to determine whether or not their attention to visual stimuli that are social or non-social in nature, matches the behavior of their performance in the castle,” said Thompson.

Thompson hopes her research, funded by the Corewell Health-MSU Alliance, MSU C-RAIND, and the Mall Family Foundation, will provide insight into types of intervention strategies that will be helpful for children with autism and hopes to publish findings related to social motivation in the next year or two.

“It could provide insight into how the child interprets those attempts at connection and help the people around them better understand how the child feels about that social interaction,” said Thompson. “That could lead the family, friends and community to consider their own behaviors while interacting with the child. Really, the benefit to the parent/child is advancing science forward.”

To learn more about participating in the research at the SEND lab, click here.

By Emily Linnert